Breathwork Fundamentals Part I: Speed vs. Depth

In this four-part series, we’ll dive into the fundamental variables across all breathwork styles. When combined and altered, these variables create a specific desired outcome.

Today we’re focusing on speed (or time) and depth of breath.

Speed/Time

Speed is defined by how quickly or slowly we breathe. It can also be synonymous with time or duration of a breath. The speed or pace by which we breathe can also alter how deeply we breathe. When we breathe quickly such as with breath of fire, it can be hard to find full, deep belly breaths, which is to be expected, as the intention is on a short inhale with emphasis on a forceful, rapid exhale.

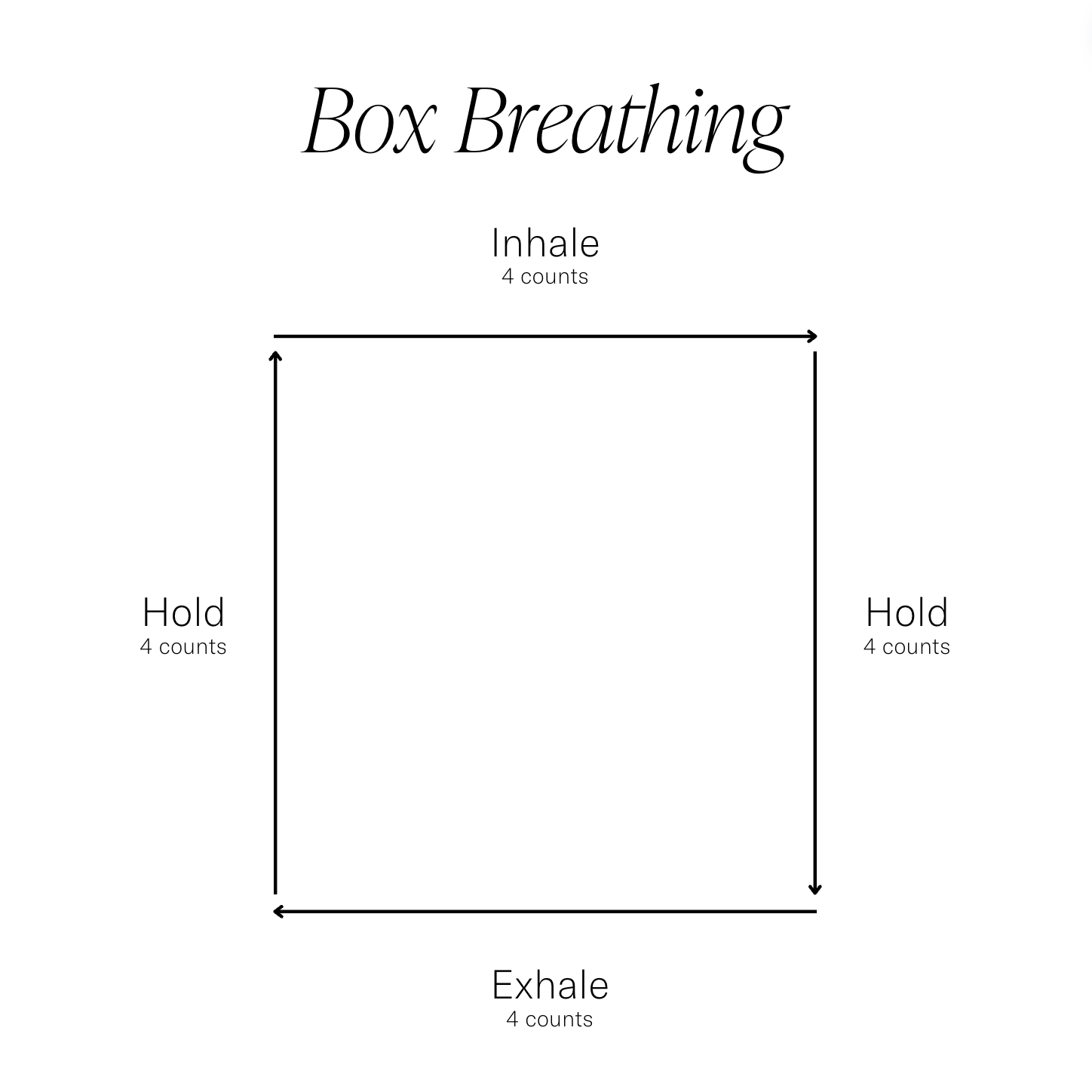

Styles such as box-breathing or coherent breath focus on a set time duration assigned to the breath including the inhales, exhales, and any use of breath holds. For instance with box-breathing, the breath pattern follows a rhythm where the amount of time dedicated to the inhale, hold, exhale and final hold are equal (also pictured in the diagram below):

4 counts in

4 counts hold the breath at the top (lungs full of air)

4 counts breathe out

4 counts hold the breath at the bottom (lungs empty).

What happens when we breathe quickly?

Rapid breathing can be a natural response to certain situations, such as during exercise, needing to flee a dangerous situation, or when experiencing strong emotions. When we breathe quickly, our sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) is activated leading to increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and possible feelings of anxiety or tension. Chronic or prolonged rapid breathing can contribute to heightened stress levels and may exacerbate conditions such as anxiety disorders.

When we breathe quickly, we’re also prone to breathing more shallowly, focusing predominantly on expanding/contracting within the chest cavity rather than engaging the diaphragm (ie. breathing deeply into the belly). Shallow breathing can limit the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs, potentially leading to decreased oxygenation of tissues and increased feelings of breathlessness or discomfort.

What happens when we breathe slowly?

Slowing down our breathing activates our parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest) signaling our bodies and the muscles around our chest, abdomen and diaphragm to relax. Our heart rate decreases along with our blood pressure, encouraging a sense of calm, allowing better cognitive function and our minds to find greater levels of mindfulness and concentration.

When we breathe slowly, it also allows our bodies to more efficiently exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide (through our respiration), allowing our bodies to maintain a balanced pH in the blood, promoting greater O2 delivery to our tissues and organs.

Depth

Diaphragmatic engagement explained

Diaphragmatic engagement means using your diaphragm, which is a large muscle located beneath your lungs, to help you breathe deeply and efficiently. When you inhale, your diaphragm contracts and moves downward, creating space in your chest cavity for your lungs to expand. This allows you to take in more air and oxygen.

To engage your diaphragm while breathing, on your inhale, imagine filling your belly with air like a balloon and witness it expand in 360 degrees. On your exhale, allow the breath to release with ease and notice how the belly naturally deflates as the air leaves your lungs.

What are the benefits of breathing deeply?

Deep breathing helps optimizes the efficiency of the respiratory process and promotes various physiological benefits such as:

Increased Lung Expansion: The diaphragm is the primary muscle responsible for breathing. When it contracts during inhalation, it moves downward, creating a vacuum in the chest cavity that allows the lungs to expand fully. Deep diaphragmatic breathing ensures maximum lung expansion, allowing for greater oxygen intake and carbon dioxide expulsion.

Improved Gas Exchange: Deep diaphragmatic breathing facilitates more effective gas exchange in the lungs. By maximizing lung expansion, it increases the surface area available for oxygen to diffuse into the bloodstream and for carbon dioxide to be expelled from the body. This helps maintain optimal blood oxygenation levels and facilitates the removal of waste gases.

Enhanced Relaxation Response: Deep diaphragmatic breathing stimulates the vagus nerve, which plays a key role in activating the parasympathetic nervous system, the body's "rest and digest" response. Activation of the parasympathetic nervous system promotes relaxation, reduces stress hormones like cortisol, lowers heart rate, and enhances feelings of calm and well-being.

Improved Posture and Core Stability: Deep diaphragmatic breathing encourages proper alignment of the spine and ribcage, promoting good posture and core stability. When the diaphragm contracts fully, it engages the deep core muscles, including the transverse abdominis and pelvic floor muscles. This helps support the spine and pelvis and contributes to overall stability and balance.

Reduced Respiratory Effort: Deep diaphragmatic breathing can help alleviate the strain on accessory respiratory muscles, such as those in the neck and shoulders, which may become overused during shallow breathing patterns. By utilizing the diaphragm effectively, breathing becomes more efficient and requires less effort, reducing fatigue and promoting relaxation.

In summary, deep diaphragmatic engagement during breathing optimizes respiratory function, promotes relaxation, enhances oxygenation, and contributes to overall physical and mental well-being. Practicing deep breathing exercises regularly can help cultivate a more mindful and balanced breathing pattern, leading to various long-term health benefits.

The science of deep breathing tied to lung capacity and longevity

One measure of lung function is vital capacity, which is the maximum amount of air a person can exhale after taking the deepest breath possible. Vital capacity tends to decrease with age due to a combination of factors such as changes in lung elasticity, muscle strength, and the effects of conditions like arthritis which may restrict chest movement.

The rate and extent of decline can vary among individuals and are influenced by factors such as genetics, lifestyle, and environmental exposures. Generally, after the age of 30, lung function starts to decline at a rate of about 1% per year (Source: American Lung Association). This means that between the ages of 30-50, a person’s lung capacity can drop by 20%!

Reduction in lung capacity can result in the following symptoms:

shortness of breath

lower energy, decreased stamina and endurance

decline in general focus, memory and concentration

susceptibility to respiratory illnesses

impaired metabolic and digestive functions

Many studies have research the ties between lung capacity and longevity including "Vital Capacity as a Predictive Indicator of Longevity: A Follow-up Study" by Y. Nakata et al., published in The American Journal of Epidemiology in 2000. This study followed a large cohort of Japanese men and women over several years and found that vital capacity, was positively associated with longevity. Individuals with higher vital capacity tended to live longer than those with lower vital capacity, even after controlling for other factors such as age and smoking status.

Luckily, just like how exercise strengthens our muscles and bones, we can mitigate the reduction in lung capacity over time through breathwork practices that promote diaphragmatic engagement.

It’s important to consider the desired outcome you’re looking to affect when considering speed/pace or depth. Not all cases or situations will require slow breathing, and vice versa. The intention depends on context. With faster breathing styles, it’s also best recommended to practice while stationary/seated either on a chair, bed or floor, and cautioned against practicing while in a moving vehicle or while swimming/in water to avoid the risk of injury or drowning from possible lightheadedness that may arise during this type of breathing style.